You can make your essay more persuasive by getting straight to the point.

In fact, that's exactly what we did here, and that's just the first tip of this guide. Throughout this guide, we share the steps needed to prove an argument and create a persuasive essay.

Key takeaways:

- Proven process to make any argument persuasive

- 5-step process to structure arguments

- How to use AI to formulate and optimize your essay

"Write an essay that persuades the reader of your opinion on a topic of your choice."

You might be staring at an assignment description just like this 👆from your professor. Your computer is open to a blank document, the cursor blinking impatiently. Do I even have opinions?

The persuasive essay can be one of the most intimidating academic papers to write: not only do you need to identify a narrow topic and research it, but you also have to come up with a position on that topic that you can back up with research while simultaneously addressing different viewpoints.

That’s a big ask. And let’s be real: most opinion pieces in major news publications don’t fulfill these requirements.

The upside? By researching and writing your own opinion, you can learn how to better formulate not only an argument but the actual positions you decide to hold.

Here, we break down exactly how to write a persuasive essay. We’ll start by taking a step that’s key for every piece of writing—defining the terms.

A persuasive essay is exactly what it sounds like: an essay that persuades. Over the course of several paragraphs or pages, you’ll use researched facts and logic to convince the reader of your opinion on a particular topic and discredit opposing opinions.

While you’ll spend some time explaining the topic or issue in question, most of your essay will flesh out your viewpoint and the evidence that supports it.

If you’re intimidated by the idea of writing an argument, use this list to break your process into manageable chunks. Tackle researching and writing one element at a time, and then revise your essay so that it flows smoothly and coherently with every component in the optimal place.

This is probably the hardest step. You need to identify a topic or issue that is narrow enough to cover in the length of your piece—and is also arguable from more than one position. Your topic must call for an opinion, and not be a simple fact.

It might be helpful to walk through this process:

That answer is your opinion.

Let’s consider some examples, from silly to serious:

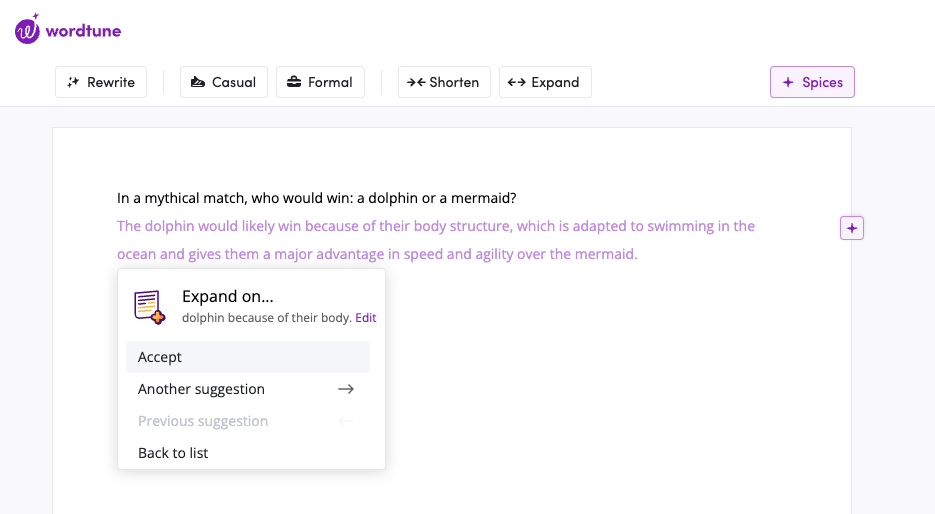

Topic: Dolphins and mermaids

Question: In a mythical match, who would win: a dolphin or a mermaid?

Answer/Opinion: The mermaid would win in a match against a dolphin.

Topic: Autumn

Question: Which has a better fall: New England or Colorado?

Answer/Opinion: Fall is better in New England than Colorado.

Topic: Electric transportation options

Question: Would it be better for an urban dweller to buy an electric bike or an electric car?

Answer/Opinion: An electric bike is a better investment than an electric car.

Your turn: Walk through the three-step process described above to identify your topic and your tentative opinion. You may want to start by brainstorming a list of topics you find interesting and then going use the three-step process to find the opinion that would make the best essay topic.

If you walked through our three-step process above, you already have some semblance of a thesis—but don’t get attached too soon!

A solid essay thesis is best developed through the research process. You shouldn’t land on an opinion before you know the facts. So press pause. Take a step back. And dive into your research.

You’ll want to learn:

As you learn the different viewpoints people have on your topic, pay attention to the strengths and weaknesses of existing arguments. Is anyone arguing the perspective you’re leaning toward? Do you find their arguments convincing? What do you find unsatisfying about the various arguments?

Allow the research process to change your mind and/or refine your thinking on the topic. Your opinion may change entirely or become more specific based on what you learn.

Once you’ve done enough research to feel confident in your understanding of the topic and your opinion on it, craft your thesis.

Your thesis statement should be clear and concise. It should directly state your viewpoint on the topic, as well as the basic case for your thesis.

Thesis 1: In a mythical match, the mermaid would overcome the dolphin due to one distinct advantage: her ability to breathe underwater.

Thesis 2: The full spectrum of color displayed on New England hillsides is just one reason why fall in the northeast is better than in Colorado.

Thesis 3: In addition to not adding to vehicle traffic, electric bikes are a better investment than electric cars because they’re cheaper and require less energy to accomplish the same function of getting the rider from point A to point B.

Your turn: Dive into the research process with a radar up for the arguments your sources are making about your topic. What are the most convincing cases? Should you stick with your initial opinion or change it up? Write your fleshed-out thesis statement.

This is a typical place for everyone from undergrads to politicians to get stuck, but the good news is, if you developed your thesis from research, you already have a good bit of evidence to make your case.

Go back through your research notes and compile a list of every …

… or other piece of information that supports your thesis.

This info can come from research studies you found in scholarly journals, government publications, news sources, encyclopedias, or other credible sources (as long as they fit your professor’s standards).

As you put this list together, watch for any gaps or weak points. Are you missing information on how electric cars versus electric bicycles charge or how long their batteries last? Did you verify that dolphins are, in fact, mammals and can’t breathe underwater like totally-real-and-not-at-all-fake 😉mermaids can? Track down that information.

Next, organize your list. Group the entries so that similar or closely related information is together, and as you do that, start thinking through how to articulate the individual arguments to support your case.

Depending on the length of your essay, each argument may get only a paragraph or two of space. As you think through those specific arguments, consider what order to put them in. You’ll probably want to start with the simplest argument and work up to more complicated ones so that the arguments can build on each other.

Your turn: Organize your evidence and write a rough draft of your arguments. Play around with the order to find the most compelling way to argue your case.

You can’t just present the evidence to support your case and totally ignore other viewpoints. To persuade your readers, you’ll need to address any opposing ideas they may hold about your topic.

You probably found some holes in the opposing views during your research process. Now’s your chance to expose those holes.

Take some time (and space) to: describe the opposing views and show why those views don’t hold up. You can accomplish this using both logic and facts.

Is a perspective based on a faulty assumption or misconception of the truth? Shoot it down by providing the facts that disprove the opinion.

Is another opinion drawn from bad or unsound reasoning? Show how that argument falls apart.

Some cases may truly be only a matter of opinion, but you still need to articulate why you don’t find the opposing perspective convincing.

Yes, a dolphin might be stronger than a mermaid, but as a mammal, the dolphin must continually return to the surface for air. A mermaid can breathe both underwater and above water, which gives her a distinct advantage in this mythical battle.

While the Rocky Mountain views are stunning, their limited colors—yellow from aspen trees and green from various evergreens—leaves the autumn-lover less than thrilled. The rich reds and oranges and yellows of the New England fall are more satisfying and awe-inspiring.

But what about longer trips that go beyond the city center into the suburbs and beyond? An electric bike wouldn’t be great for those excursions. Wouldn’t an electric car be the better choice then?

Certainly, an electric car would be better in these cases than a gas-powered car, but if most of a person’s trips are in their hyper-local area, the electric bicycle is a more environmentally friendly option for those day-to-day outings. That person could then participate in a carshare or use public transit, a ride-sharing app, or even a gas-powered car for longer trips—and still use less energy overall than if they drove an electric car for hyper-local and longer area trips.

Your turn: Organize your rebuttal research and write a draft of each one.

You have your arguments and rebuttals. You’ve proven your thesis is rock-solid. Now all you have to do is sum up your overall case and give your final word on the subject.

Don’t repeat everything you’ve already said. Instead, your conclusion should logically draw from the arguments you’ve made to show how they coherently prove your thesis. You’re pulling everything together and zooming back out with a better understanding of the what and why of your thesis.

A dolphin may never encounter a mermaid in the wild, but if it were to happen, we know how we’d place our bets. Long hair and fish tail, for the win.

For those of us who relish 50-degree days, sharp air, and the vibrant colors of fall, New England offers a season that’s cozier, longer-lasting, and more aesthetically pleasing than “colorful” Colorado. A leaf-peeper’s paradise.

When most of your trips from day to day are within five miles, the more energy-efficient—and yes, cost-efficient—choice is undoubtedly the electric bike. So strap on your helmet, fire up your pedals, and two-wheel away to your next destination with full confidence that you made the right decision for your wallet and the environment.

Once you have a draft to work with, use these tips to refine your argument and make sure you’re not losing readers for avoidable reasons.

If you want to win people over to your side, don’t write in a way that shuts your opponents down. Avoid making abrasive or offensive statements. Instead, use a measured, reasonable tone. Appeal to shared values, and let your facts and logic do the hard work of changing people’s minds.

You can use AI to turn your general point into a readable argument. Then, you can paraphrase each sentence and choose between competing arguments generated by the AI, until your argument is well-articulated and concise.

Make sure the facts you use are actually factual. You don’t want to build your argument on false or disproven information. Use the most recent, respected research. Make sure you don’t misconstrue study findings. And when you’re building your case, avoid logical fallacies that undercut your argument.

A few common fallacies to watch out for:

The strongest arguments rely on trustworthy information and sound logic.

We recently wrote a three part piece on researching using AI, so be sure to check it out. Going through an organized process of researching and noting your sources correctly will make sure your written text is more accurate.

If you’re building a house, you start with the foundation and go from there. It’s the same with an argument. You want to build from the ground up: provide necessary background information, then your thesis. Then, start with the simplest part of your argument and build up in terms of complexity and the aspect of your thesis that the argument is tackling.

A consistent, internal logic will make it easier for the reader to follow your argument. Plus, you’ll avoid confusing your reader and you won’t be unnecessarily redundant.

The essay structure usually includes the following parts:

Persuasive essays are a great way to hone your research, writing, and critical thinking skills. Approach this assignment well, and you’ll learn how to form opinions based on information (not just ideas) and make arguments that—if they don’t change minds—at least win readers’ respect.